These days, many social workers are pretty clear that anti-racism is something they need to consistently work on in their practice, but when it comes to ableism, well, that’s something else altogether. Let’s start with a quick definition of ableism to build our disability competence a bit. Disability activists Talila Lewis and Dustin Gibson frame ableism as “a system that places value on people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, intelligence, excellence, and productivity.” But seriously, ableism, you may say…what has that got to do with racism? Why are we even talking about this?

It turns out, ableism and racism are related, and quite strongly. In fact, Dr. Ibram X. Kendi himself, host of the podcast Be antiracist and author of the book How to be an antiracist, says “It is pretty apparent to me that one cannot be anti-racist while still being ableist…I think for many people who are indeed striving to be anti-racist they may not realize the ways in which they’re still being prevented from moving along on this journey due to their unacknowledged or unrecognized ableism, or the ways in which they’re in denial.”

Social Work, Race, & Disability

As we begin to break this down, as a disabled woman, I’d like for our profession to own that social work often forgets to realize the disability community in diversity considerations. And with this, is a failure to see ableism, despite the fact that we, the disability community, comprise 26 percent of the U.S. population – that’s 1 in 4 Americans according to the Centers for Disease Control. And if you consider the racial and ethnic diversity within the disability community (and vice versa if we are being intersectional) then we need to be considering how ableism and racism interact and intersect.

Let’s just start with the basic demographics. A recent study on disability, race and ethnicity tells us that 1 in 4 members of the Black and African American communities have a disability, while 1 in 6 members of the Hispanic/Latinx communities do. In the American Indian and Alaskan Native communities, it is 3 in 10, and among Asian and Pacific Islander communities, it is 1 in 10 and 1 in 6, respectively.

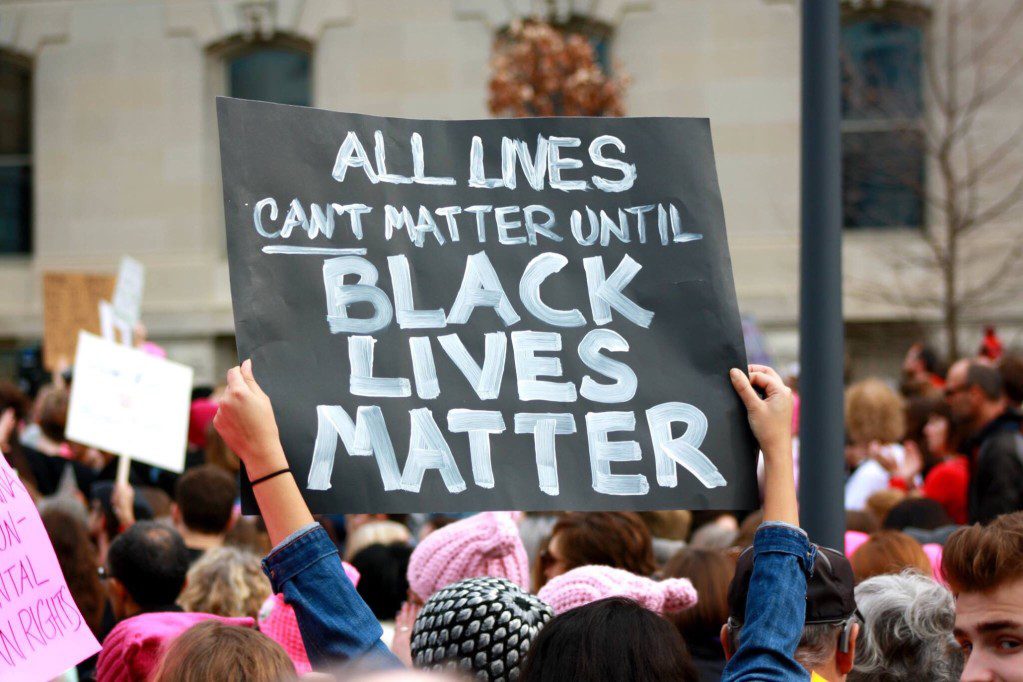

When we start to look at social issues connected to these types of data points, we find out bits of information such as the fact that people of color with disabilities have higher rates of unemployment than do their White counterparts, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Then there are the realities that many school social workers have seen in classrooms nationwide for decades, with disproportionate numbers of students of color being sent into special education. And in the post George Floyd era, we are also more aware of the connection between racism and ableism due to the fact that 50 percent of people killed during encounters with police in a two year period were people of color with disabilities, as the Ruderman Family Foundation documented in their landmark report.

The Impact of the Pandemic

Then we have the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately impacted communities of color. We know that initial research suggests that about one third of people who had the virus will develop what is called “long COVID” which will now be classified as a disability. According to disability justice activist Rebecca Cokely, that means that we will be adding an estimated ten million people to the disability community who will be covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. This law provides workplace and other protections for disabled people – although the implementation and enforcement of this law is far from perfect, and thus the cycle of ableism and racism starts again given the overrepresentation of people of color in this population.

These are just a few current-day snippets that tell us we need to be paying attention to both ableism, racism and the ways in which these two forms of oppression are related to one another. Ableism and racism exist in a symbiotic relationship, with each acting as the tool of the other. Being aware of the intersection between racism and ableism is part of how social workers can begin to disrupt this reality in their practice and in their larger communities. So, what can you do to be more aware of racism and ableism in your social work practice? You can start by paying attention to the disability side of the equation that often gets forgotten! Here are some activities for you to consider as you engage in this vital social justice work:

- Start by exploring your able-bodied privilege. Read the following prompts on able-bodied privilege from the Autistic Hoya blog, written by Autistic disability justice activist and lawyer Lydia X. Z. Brown. Which items were most salient to you? You may consider the list items from a personal and/or a professional perspective, focusing on how you may or may not experience these issues yourself or how you may have encountered these issues as a social worker. How do race and ethnicity factor into able-bodied privilege?

- Continue by building your personal disability awareness. What values and/or ideas do you hold that may unconsciously perpetuate ableism? Where did you pick up these values? How does this play out with your disabled clients of color? Take time to think these questions out, and be mindful of them as you move forward.

- Just as it is super important to acknowledge our potential for racism as people raised in a racist society, so too is it important to acknowledge the ways we may have engaged in the use of ableist language or expression of ableist attitudes. How have you or your agency/organization/company unconsciously or consciously used ableist language, or expressed ableist attitudes? How do race and ethnicity factor in here? How can you change things moving forward?

This article has demonstrated the connections between disability and race, but social work has often failed to see disability. How can you look at the causes you are already involved in through a disability framework that is also attentive to race and ethnicity? How can you lift up the disability perspective and promote disability empowerment while being anti-racist?